4th Annual Harper Cancer Research Institute Research Day 2015

By John Fineran

Around the Mike and Josie Harper Cancer Research Institute on the campus of the University of Notre Dame, there is this basic belief: Teamwork can make a dream work.

If you’re bringing your silo mentality to the workshop, you’d best leave it at the door. Or to put it in terms people can appreciate at Notre Dame – you need to share the football to get it into the end zone.

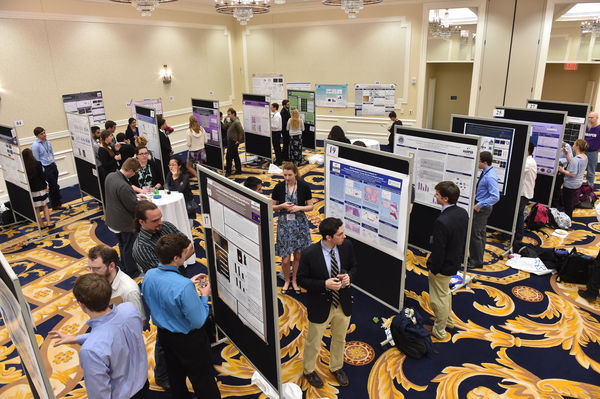

Since its inaugural year in 2012, the Harper Cancer Research Institute (HCRI) invites all members from the Notre Dame and Indiana University School of Medicine- South Bend community to gather together and share their work. This spring, HCRI celebrated its 4th annual Research Day-- and it was bigger and better than ever. The Morris Inn Ballroom was packed full during the poster session, which consisted of not only the 91 poster presenters from 30 different laboratories, but also those from the community who are interested in cancer research. Following the poster session, all were invited to McKenna Hall to tune into oral presentations, a discussion of career opportunities led by a panel from Eli Lilly and Co. and Keynote by Lynn Matrisian, Vice President for Research and Medical Affairs at Pancreatic Action Network. It truly was a day to collaborate and learn about the research being conducted on campus.

“Here at Notre Dame and the Harper Cancer Research Institute, they are really good in promoting collaborative research,” said Katherine Richards, a graduate student in the Department of Biological Sciences who is trying to unlock the mysteries of pancreatic cancer, which is predicted to be the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths by the year 2020.

Richards was one of several researchers who presented posters of their work at the institute’s annual Research Day and you don’t have to sell her on the benefits of different science, mathematical and engineering disciplines working together. She has already bought in.

“What I presented was not only the work I was involved in but it required the work of engineers,” added Richards, a molecular biologist. “You’ll notice there are people who are studying physics, people who are studying mathematics, biologists like us and engineers. More and more, we’re learning from each other and it’s going to take that collaborative effort to come up with treatments that work and the technology that gives us the tools for early detection.”

In the case of pancreatic cancer, the signs that detect the disease aren’t apparent in most cases until it’s too late. Most patients receive their diagnosis when the cancer is in its late stages and by then the survival rate is often less than a year. When it comes to detection of any cancer, earlier is always better.

Ian Guldner, a second-year graduate student in biology, has been working with computer scientists and engineers at Notre Dame to try and find out how and why tumors develop and grow in the brains of breast cancer patients. This collaboration has led to what is called tissue clearing.

“One of the biggest issues in terms of the brain is lipids, which has prevented us from getting good images of the brain,” Guldner said. “Engineers have determined how we can remove lipid and not everything else that really matters. Lipid prevents us from looking at molecular mechanisms in cells as well as the interaction between cells. Without lipid removal, we don’t get a 3D perspective. Engineers have been the driving force behind clearing the tissue and helping us achieve the 3D perspective that helps us code what happens biologically.”

Lisa Cole, a bioengineer defending her PhD., has attacked breast cancer in another way. Under the guidance of biologist Tracy Vargo-Gogola and engineer/material scientist Ryan K. Roeder, their study has developed a contrast agent that can be injected into a patient prior to a mammogram.

“We’re not trying to change mammograms – we’re trying to improve them with a contrast agent,” Cole said. “So instead of sending you for another image, an MRI or taking a biopsy, you can inject this agent and it would bind to the abnormality so it will provide the radiologist a better image.”

Peter Feist, a biochemist graduate student, is concentrating his work on colon cancer, the third-leading cause of cancer deaths every year. It is particularly prevalent in persons 50 years of age and older but usually detectable if patients undergo checkups, blood tests and colonoscopies regularly.

“Working with smaller and smaller amounts of material means that we’re able to be more sensitive in the detection, decrease the false-positive rates and increase the actual positives we need in order to catch colon cancer early,” he said. “If you can catch colon cancer early, it’s extremely survivable.”

Surviving sometimes doesn’t mean a cure but often times means another day in the fight to find one and to get others to join in that fight, which is what Dr. M. Sharon Stack, the director of the Harper Cancer Research Institute, believes is the key to fighting all cancers. She has seen how collaboration works in the cancer labs.

“A lot of the stuff we’ve been doing all along isn’t working in most cases so having a new approach is a great way to go about it,” Stack said. “You have a skill here, I have a skill here; what can we do that is better than either one of us can do alone?

“I’ve seen it working tremendously well, we’ve had a lot of buy-in from the faculty and the students. Everyone is tremendously excited about using this different approach to address questions that are important. To those of us who are biologists and biochemists, it gives us a new set of tools; to those who are engineers and physicists, it gives them a new set of challenges. So it’s a perfect match.”

For cancer patients, that light at the end of the tunnel is no longer a freight train. It is one of hope. “And it’s getting brighter every day,” Stack said, thanks to old-fashioned teamwork.