The Harper Cancer Research Institute’s new tissue bank is bringing scientists to the frontier of cancer research—and giving cancer patients a way to contribute.

SOUTH BEND, INDIANA - Lisa Stripling's cancer diagnosis arrived on August 14, 2012, as such news often arrives: without much warning and without much time to react.

The uterine and ovarian cancer in her body was a serious threat. Dr. Michael Rodriguez, Stripling’s oncologist at Michiana Hematology Oncology, recommended a complete hysterectomy as soon as possible. Even with a successful surgery, Stripling would still need chemotherapy and both internal and external radiation.

Yet in a way, Stripling’s grim diagnosis arrived in the right place at the right time. In addition to a speedy surgery, Rodriguez had a second recommendation: Stripling could be one of his first patients to donate any surgically-removed cancerous tissue to the Harper Cancer Research Institute, where it they would be stored in a tissue bank and used for cancer research.

“When I had my surgery on August 23, 2012, it was right around when [Harper] started tissue banking,” she says. “I can remember, prior to surgery, signing a form that said anything removed could be donated to research.”

Stripling’s surgery was successful, and a portion of the removed tissue was sent to Harper. But the chemotherapy treatments were grueling. At the recommendation of one of her nurses, she visited RiverBend Cancer Services in South Bend, where she found another ally in Laura Ginter. RiverBend is solely dedicated to helping patients cope with the side effects of their treatments. Ginter is RiverBend’s program director and welcomed Stripling to a community of fellow cancer patients.

“That’s one thing with Laura—she knows what to do to make people feel comfortable and involved,” Stripling says. “Anything that you might need that you can’t afford, or that insurance won’t pay for, they help with. Bras for women who have had mastectomies. Wigs for women who are starting to lose their hair.”

In April 2013, Stripling met Dr. Sharon Stack, the Ann F. Dunne and Elizabeth Riley Director of the Harper Cancer Research Institute, who was visiting RiverBend to discuss tissue banking. Finally, months after Stripling’s initial diagnosis, she could connect a face with a name. Stack mentioned Rodriguez and “how he was really the first to start tissue banking at Michiana Hematology Oncology,” Stripling says.

It’s impossible to say if Stripling’s donation has been used for research. All tissue donations are de-identified, so no tissue sample can be traced to its original donor. (The institute’s staff records relevant information about the cancer, of course, including the patient’s gender or age.) But her donation is highly valuable: Human tissue is the best possible resource for cancer research.

“When we first started the tissue bank, I wanted to have it here for the researchers,” Stack says. “As a researcher, getting your hands on human tissue—to validate your model systems, make sure your questions are accurate, that your models are accurately representing the diseases you’re studying—is the single hardest thing to do. I wanted to do this to make that easy.”

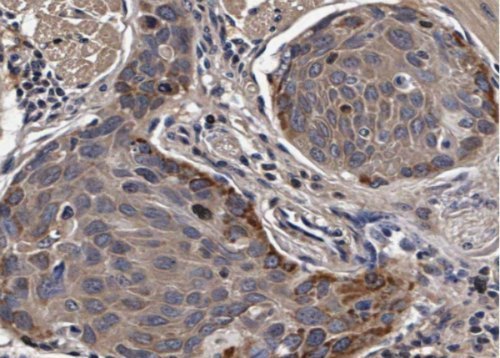

And even though Stripling’s tissue donation remains anonymous, a number of research projects at Harper could benefit from her contribution. Dr. Karen Cowden Dahl, an ovarian cancer specialist, uses tissue samples to study a gene called ARID3B, which seems to affect ovarian cancer’s resistance to chemotherapy. “Most people respond very well to treatment, but some will relapse,” Cowden Dahl says. “We can stop [the cancer] for a while, but if it learns, there’s no stopping it.” A better understanding of the ARID3B gene may help change that.

Stack, an ovarian cancer researcher herself, studies how ovarian cancer spreads. “The cells detach from the primary tumor and eventually re-attach throughout the peritoneal cavity,” she says. Understanding that pattern of detachment and adhesion is critical, because the adhesion enables breakaway cells to eat away at healthy tissue. “Once we understand what’s happening in that adhesion, then we’ll understand what to target.”

Stripling’s tissue donation was ahead of the curve. Because Harper is unaffiliated with a research hospital, acquiring tissue donations can be a logistical challenge.

“Initially, nobody knew who we were or what we were about,” Stack says. “It took a while for them to understand that we’re all in it for the same reason.”

So Stack has partnered with private pathology groups like The Medical Foundation in South Bend to gather tissue donations that would otherwise be discarded as medical waste. She also works with individual doctors like Rodriguez, Harper’s formal ‘Tissue Banking Champion’.

“It’s a completely unique model of how to do a tissue bank, and it’s extremely challenging,” she says. “But the more that the community physicians and their teams and patients know about it, the more they’re happy to participate…There’s no reason not to.”

And with the tissue bank gaining recognition among area oncologists, Stack has hired two specialists to work with Dr. Zonggao Shi, a scientist experienced in research pathology who directs the tissue bank. Toni Page-Mayberry, the tissue bank consent coordinator and a cancer survivor herself, works one-on-one with surgeons and patients to guide them through the donation process. Tissue technician Laura Tarwater retrieves donations from clinics, logs relevant medical data, de-identifies the samples for patient confidentiality, and stores the samples.

For all the good tissue donations do in the laboratory—and they are tremendously valuable to researchers—there’s another reason Stack is so dedicated to reaching out to local doctors and patients.

“It’s empowering for cancer patients with this diagnosis to be able to contribute to biomedical research,” Stack says. “It’s a positive thing that they can do.”

Now in remission for over a year, Stripling agrees.

“As I see it, anything that you can provide is helping maybe find better treatments, a cure of some kind,” Stripling says. “I would definitely recommend donating if you have a chance. If something good can come from something bad, then I’m all for that research.”

By Michael Rodio