Tweaking the immune system with therapies to target and kill cancer cells has been a promising advancement for cancer research, but the current methods used by many companies can unintentionally destroy healthy tissues as well.

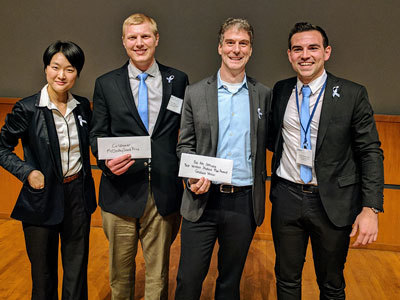

The interdisciplinary team of Structured Immunity, however, has patented a new technology that can increase drug efficacy and lessen the possibility of these side effects. The start-up shared the grand prize in the McCloskey Business Plan competition in April. Structured Immunity was guided by Brian Baker, the John A. Zahm Professor of Structural Biology and chair of the department of chemistry and biochemistry, and researcher with the Mike and Josie Harper Cancer Research Institute, and was developed by David Hardwicke, ESTEEM ’17, Tim Riley PhD. ’17, and Fan Ping, MBA ’17.

The prize came with a $15,000 award, but it’s the exposure to investors that is particularly exciting to the winning team as they now look toward assembling a board of directors and launching their company.

“We had a diverse team with many skill sets, and this aids to the pace of getting a business started,” said Hardwicke. “Last July when I first met Brian and Tim, this was a promising technology in the research phase. But now it’s a promising startup with an innovative business model—it’s very exciting.”

The field of T-cell therapy involves engineering T-cells of the human immune system to target and destroy cancer cells. T-cells are the subtype of a white blood cell responsible for sensing whether you’re healthy, if you have an infection, or even if you have cancer. To accomplish this, researchers engineer a molecule within T-cells called a T-cell receptor (TCR). T-cell therapy centers on editing TCRs to supercharge the natural power of the immune system.

Structural biology is a relatively mature field, according to Riley, and immunology is even older. However, “the intermixing of these two disciplines has only just begun,” he said, adding that Structured Immunity’s science and technology brings together the two fields in new ways.

“It’s the kind of thing when I think about it, I realize, wow, this really is the 21st century, because it’s almost science fiction,” Baker said. “And for many years people said it was fiction, but it actually is happening.”

One of the challenges scientists face is when they tweak the immune system, they could unintentionally engineer the TCR to target a healthy cell in addition to a cancer cell, Baker said. “And that’s a potentially massive problem. So one of the main issues that we’ve been studying is how can you circumvent that; how can you engineer these T-cells to be more specific toward what we call a tumor antigen?” he said.

Structured Immunity earned its name because its patented technology uses a process of structure-based, guided protein design to reengineer the TCR. With this method, the researchers take a three-dimensional “snapshot” of the TCR and use this picture – or 3D structure – to optimize it. In their process, pharmaceutical companies that develop T-cell therapies (there are more than 280 in the pipeline, according to Hardwicke) will send Structured Immunity their TCRs, and scientists with Structured Immunity will make these fine molecular optimizations. Companies might start with dozens, even hundreds of molecules, but need to know which ones won’t work as planned. The current process, which Structured Immunity hopes to circumvent, can take years and costs tens of millions of dollars.

“With a potential pharmaceutical company partner, Structured Immunity will say, look, we can help whittle your list down,” Riley said. “Structured immunity can take your molecules of interest and make them better so you don’t have to go through this exhaustive, expensive phase of trying to find the best molecule.”

Structured Immunity will run calculations, rank the results based on how accurately they’ll target cancer cells vs. other cells, test them, and send the pharmaceutical company a blueprint of the molecule—essentially the DNA sequence and accompanying data, Hardwicke said.

Structured Immunity’s collaborative process between science and business has sped up the process to bring this important technology to the public, Hardwicke said. He is continuing to pitch the business concept at other conferences with hopes to land more investment dollars.

“Sometimes it is really important to acknowledge what you do not know,” Riley said, adding that reaching out to the professionals at Innovation Park, who connected him and Baker with Hardwicke and Ping, was crucial. “Although Dr. Baker’s laboratory is a leader in structural immunology, without the support of experts in sales, business, and finance, this technology would likely stay strictly academic.”

The McCloskey Business Plan Competition, sponsored by the Gigot Center for Entrepreneurship at the Mendoza College of Business, is intended for traditional entrepreneurial ventures that have not yet been launched or are at the earliest stage of launch. Both Hardwicke and Riley plan to continue working with Structured Immunity in the fall, to grow and develop the technology.

Originally published by at science.nd.edu on May 25, 2017.