Accurate mammography is crucial for early detection of breast cancer, which can greatly increase survival rates. Lisa Cole, a bioengineering PhD candidate, has developed an x-ray contrast agent that can detect microcalcifications more accurately. Working alongside Dr. Ryan Roeder, Associate Professor in the Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, Cole has previously experimented this new technology using in vitro and mouse models.

What’s the next step for Cole’s project? The x-ray contrast agent needs to be tested using a model that mimics actual human tissue.

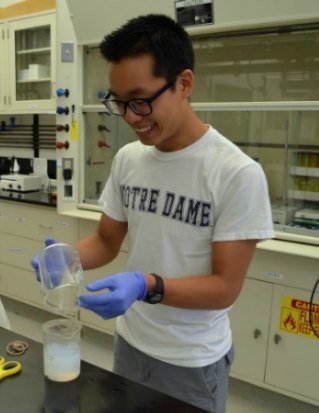

That’s where undergraduate Tony Stedge comes in. Stedge is working in Dr. Ryan Roeder’s lab doing research funded by the Harper Cancer Research Institute Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (HCRI SURF). Stedge is a junior mechanical engineering major, and he is creating an anatomically correct model for Cole’s project.

“[Cole] did a lot of modeling with gels and matrices. She then went to mouse models; the next step before human clinical trials is experimenting on anatomically correct models,” Stedge said.

Stedge is working on creating a model that is both relatively inexpensive and realistic for modeling human characteristics. Researchers use phantoms, which are substitutes of actual human tissue. Stedge’s project is to create a phantom currently unavailable on the market.

“Commercial phantoms only account for adipose tissue. We want to model both the adipose and the fibroglandular parts of the tissue,” Stedge said.

How does he do this exactly?

“I work with a x-ray micro-CT, which allows us to see what materials accurately mimic tissue. I’ve worked with polyvinyl alcohol mixtures with ethanol or just agarose gels and water to test and see if they mimic human tissue,” Stedge said.

Because models that

mimic adipose tissue already exist on the market, Stedge is focused on finding a material sufficient to model the fibroglandular part of the tissue.

“We have a lot of things that would pretty closely mimic the fatty part of the tissue, so that is where my research comes in: trying to find that fibroglandular tissue,” Stedge said.

Stedge is one of many examples of how an engineering background can contribute to the fight against cancer.

“That’s what interested me. Of course, every kid grows up wanting to cure cancer. To say that I’m working toward that end goal of cancer, at least in some form is pretty cool. I never thought I’d get that opportunity,” Stedge said.