by Michael Rodio

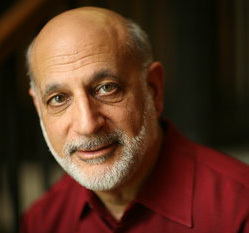

Notre Dame psychology professor Tom Merluzzi studies how cancer patients and cancer survivors find coping resources and the spiritual strength to overcome their sickness.

It’s not unusual to hear cancer researchers talk about how cancer has impacted their lives. For many, the disease looms like a specter, both inspiring their work and reminding them of the countless lives it affects.

For Dr. Tom Merluzzi, the director of Notre Dame’s Laboratory for Psycho-oncology Research and a researcher at the Harper Cancer Research Institute, cancer was not so much a specter as a deeply personal trial. In 1980, his first wife, then only 34 years old, developed a rare and aggressive form of breast cancer. Three years later, doctors discovered that Merluzzi’s mother had leukemia. But his devastation at the two diagnoses quickly yielded to something like admiration, as he watched his wife and mother summon quiet hope and courage during years of treatments.

So Merluzzi, who had spent the first part of his now four-decade-long career at Notre Dame studying social anxiety, decided to understand how cancer patients psychologically cope with the challenges of cancer and cancer treatments.

But he avoids the self-portrait as some crusader drowning his sorrows in work. Decades passed before he spoke about the personal experiences publicly. He still hesitates to define himself by it, even as it has defined his research.

“It occurred to me [during that time] that there was something really powerful happening psychologically, and perhaps spiritually, that really made surviving this dreadful disease and its treatments something that people could actually engage in,” Merluzzi said in a 2006 interview that marked the first time he spoke publicly about his experience.

After a two-year sabbatical at Stanford University, Merluzzi returned to Notre Dame and formed research partnerships with Dr. Rafat Ansari and Dr. Robin Zon, clinical oncologists at Michiana Hematology-Oncology. He has also collaborated with two Notre Dame alumni: Dr. Michael Method ’82, a gynecological oncologist, and Dr. Patricia Stanfill Edens ’88 MBA, then the executive director of South Bend’s Memorial Regional Cancer Center.

Ansari, Zon, and a group of physicians received a grant from the National Cancer Institute for the creation of a clinical oncology program that was administered by the Northern Indiana Cancer Research Consortium (NICRC) and included several hospitals in the Michiana region.

“That grant was a huge boon to our research,” Merluzzi says. “It gave us access to patients in a way that was as good as, or even better than, being connected to a traditional medical center. And at that time, I was the only psychologist locally who was doing this research.” But Merluzzi soon realized he was in unprecedented territory: most of the research on coping was guided by practical issues, not theory backed up by solid research.

So he created the precedents. In 1997, after five years of research, he and his colleagues published the first Cancer Behavior Inventory, a theoretically-based, paper-and-pencil survey that gives doctors and researchers a quantitative assessment of how well cancer patients are psychologically coping with their cancer.

“Cancers can have many symptoms, requiring many different medical treatments,” Merluzzi says. “But there are some common themes in terms of coping that cut across many of the most common cancers.”

The Cancer Behavior Inventory has seven different scales, each covering the main issues that patients face when coping with cancer. One scale indicates how well people maintain activity and independence, like a regular routine at work or at home. Other scales look at how patients deal with treatment-related side effects or maintain hope and a positive perspective.

The Cancer Behavior Inventory has been a worldwide success. Merluzzi says it has been translated into 12 languages, and he is currently preparing a third edition of the survey for publication next year. In fact, the survey’s widespread adaptation has presented another challenge: balancing the survey’s distinctly Western perspectives on coping with contrasting cultural notions about handling stress in other countries.

In the United States, for example, cancer survivorship is often couched in distinctly aggressive terms. Americans, perhaps following the example of organizations like the Livestrong Foundation, say that someone is “fighting cancer,” that survivors “win their battles” with cancer. (A headline on the front page of Livestrong’s website: “This fight is personal.”)

Despite the popularity of such slogans, there are pitfalls. “If you lose the battle to cancer,” Merluzzi says, “are you disgraced? That’s how we think about war—you win, or you’re a loser. To some extent, when someone’s cancer comes back, they may think, ‘Well, I didn’t fight well enough. It’s a weakness I have.’ And that can be dangerous, that kind of thinking.”

That’s why Merluzzi dedicates much of his research to understanding the psychology of cancer survivorship. Even after becoming “cancer-free,” cancer survivors are indelibly changed by their experience. They have to reintegrate into society, to get back into the work-and-family routine, to rebuild the community they formed when undergoing treatment. So survivors face a unique (and uniquely challenging) host of psychological challenges. And for some people, this leads to anxiety and depression, Merluzzi says.

“Our research shows—and these are not epidemiological studies, but they’re large samples that have been replicated over and over—that 20 percent of cancer survivors are distressed. That’s not as much as patients who are in treatment [30 percent], but more than the general population [about 10 percent].”

In essence, cancer survivors are twice as likely to suffer from anxiety and depression. More troubling: Cancer survivors are often reluctant to seek psychological help, even if they need it. The problem, Merluzzi says, partially stems from the American “warrior” attitude: I can handle this; I just got through chemotherapy. But the problems go beyond personal psychology. Insurance, for example, may not cover psychological help related to cancer survivorship. And there is still a stigma in America attached to seeking psychological help.

Yet there is one particularly successful way that survivors cope with cancer, and this is where Merluzzi directs much of his research focus: religion and spirituality.

“When you talk to a cancer patient about how they cope,” he says, “usually the first two things they mention are faith and family. If they are important to patients and survivors, then we need to study them carefully.”

Now Merluzzi studies a specific way of spiritual coping called “collaborative deferring,” perhaps best explained as “putting the problem in God’s hands.” Relinquishing control might seem a counterintuitive approach. In Western culture, it smacks of giving up. But Merluzzi is quick to point out that relinquishing control is an active stance, one that often involves faith in a higher power. Moreover, he has found that it actually leads to better psychological health in survivors.

“The outcomes are quite remarkable,” he says. “We’ve found that people who say they will defer the outcome to God, or develop a partnership with God, do much better with respect to coping, quality of life, and distress than someone who believes that God has imbued them with the responsibility of managing their affairs.”

As he continues his work, Merluzzi hopes that his research could contribute to a more thorough support system for cancer patients and cancer survivors—a system that, for every patient, includes psychological care alongside chemotherapy and radiation. And with a better understanding of how faith helps patients cope with cancer, he could help them develop the same courage that he once witnessed in two cancer patients he loved.